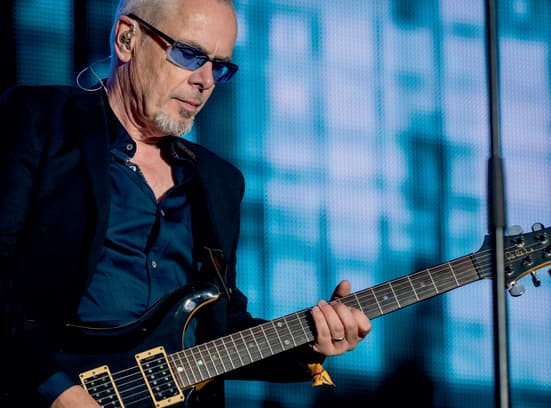

One Monday at 2.30pm, I make a sound on Desmond Morris’ front door, using the knocker resembling a dainty hand. The Naked Ape author opens up. “OX Magazine,” he says inviting me in. Aged 91, he’s relocating to Ireland, having resided in Oxford since the seventies. “The move is obviously going to be a major upheaval for me, but on the other hand, it’s a new challenge. It’s because my wife died last year; we lived here together for half a century and it just doesn’t feel right to live here without her – too many memories. And of course it’s too big for me now I’m on my own.” He’s chosen Ireland because he has family there, and has bought a house next door to his son. “Although I’m in reasonably good shape at 91, by the time I get to 92 – if I make 92 – or 93, I’m going to start needing a bit of help.” So, his boy and grandchildren will be very nearby to assist, “if I get a bit doddery”.

The process has seen him whittle down his library of 11,000 books to 3,000. “I’m keeping all the most precious ones but the empty shelves are testimony to my ruthlessness in getting numbers down.” There are “very valuable” titles that have gone to London; Mallams Auctioneers have taken some “medium value” ones off him; and other cheaper publications have been rehomed in a bookstore. “Some ended up in the skip,” the writer says, “because they were rubbish.”

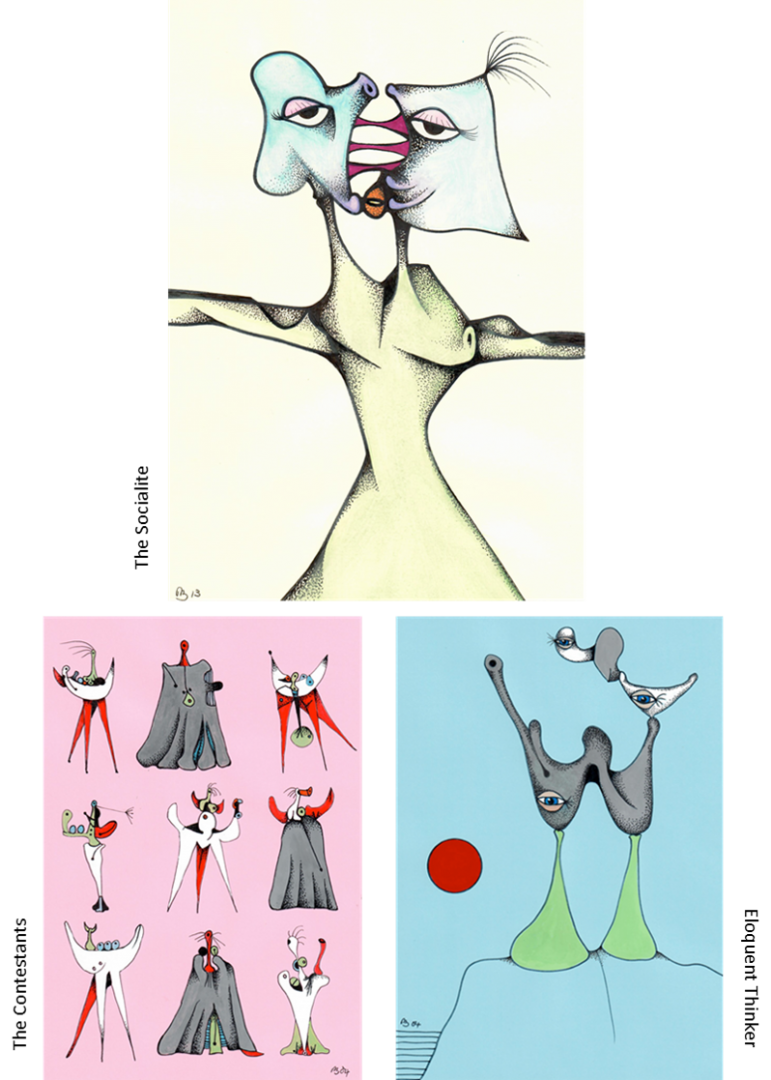

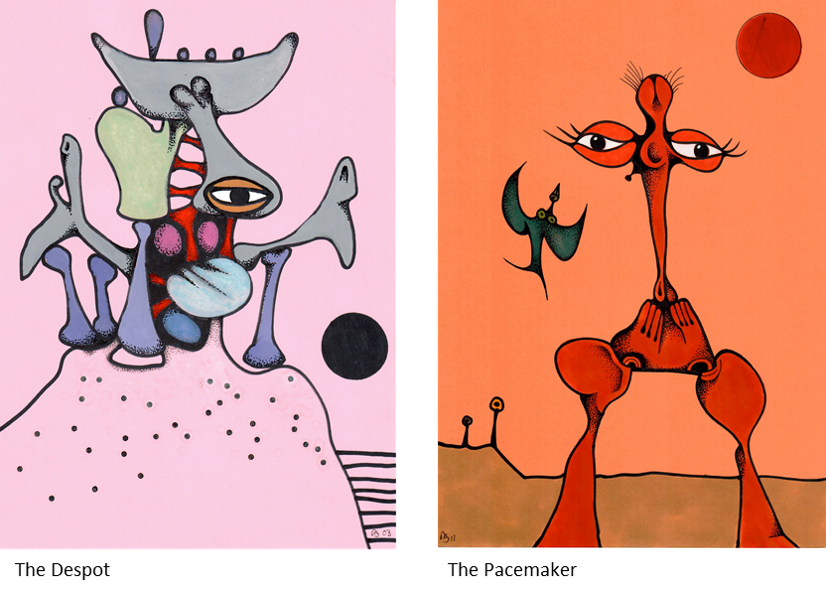

Mallams is also the venue for the surrealist painter’s latest exhibition, taking place this month. It’s the first time the auctioneers have held an art exhibition. “Benjamin Lloyd [Mallams senior director], who I think is quite pleased about the idea, said: ‘We’ll see how it goes.’ We don’t know what’s going to happen, we’ve no idea, it’s an experiment. Mallams is not an art gallery, and for that reason it’s a very short exhibition – they need the premises.” As such, there will be a private view of the show one evening, followed by just three days of public viewing. “When you have an exhibition that lasts for a month, practically all the business is done on the first few days anyway, so it’s not a big deal.”

It was suggested that it be called a farewell exhibition. “I said no because even though I’ll be in Ireland, a carload of paintings can be brought across on the ferry at any time.” The Taurus Gallery on North Parade, where he used to display work, has now closed. However, “there are other galleries here. I hope I shan’t lose touch with Oxford.”

He first came to the city in 1951, to do his doctorate in zoology at Magdalen. After a period in London, he returned in the seventies courtesy of a research fellowship, the four-year stay he’d intended becoming one of five decades. “Oxford was just so seductive, the perfect city to live in. At 91 I don’t use it as much as I used to; when I was younger I found it an absolutely marvellous city to be in. It’s still my favourite in the world. I’m not saying that because I’m sitting in Oxford – it genuinely is.” As a child growing up in Wiltshire, his family would visit the New Theatre (“a great day out”). An owner of lots of animals, he would also supply the “very grateful” Oxford Zoo with guinea pigs. “Oxford was special to me from an early age; it was the great city nearby.”

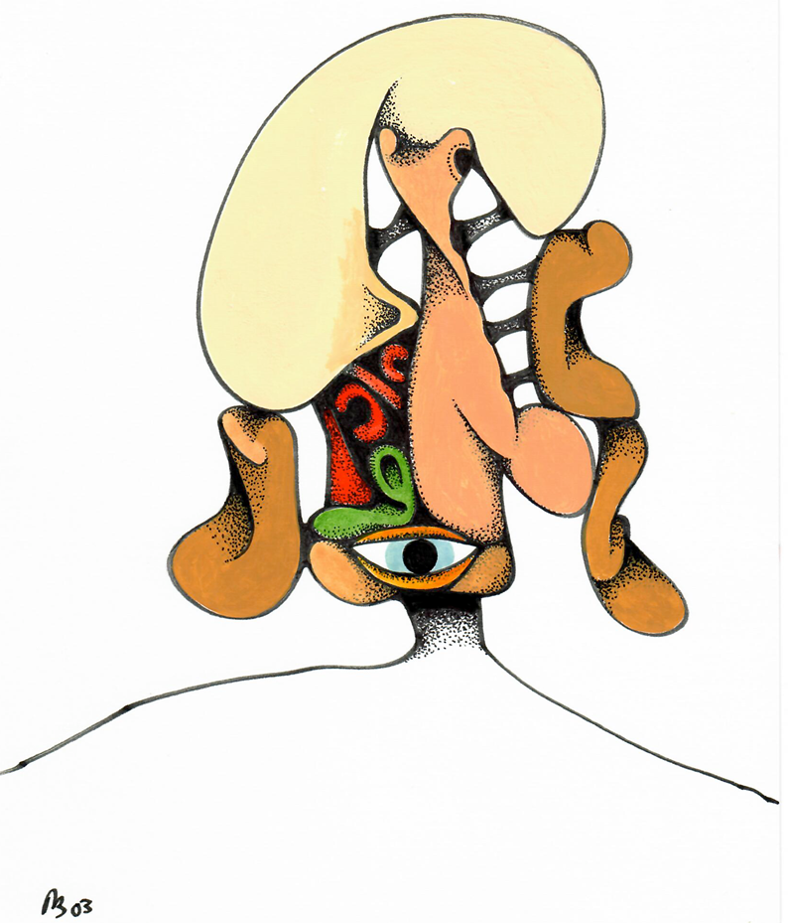

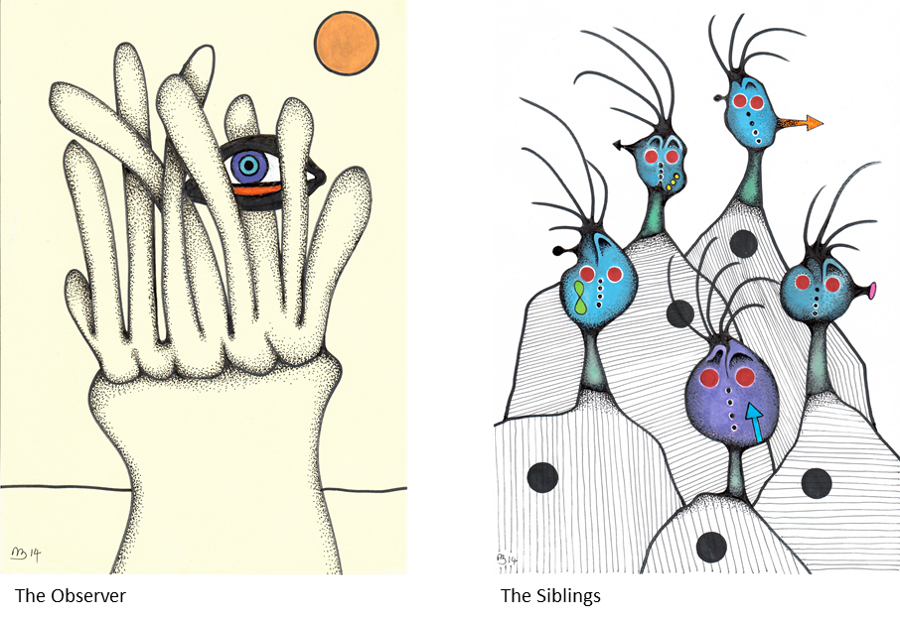

So it’s a farewell exhibition insofar as his being a resident goes, he reasons. It comprises work he’s done over the last few years. “A lot of them are very, very new,” he says, gesturing at one to my right which he completed less than a week ago. There’s a theme that ties them all together, one he’s “been following since 1947, so it’s quite old”. That year, “I was painting, influenced by Picasso and various other people, and then I suddenly decided to develop my own style of painting.” This resulted in ‘Entry to a Landscape’, he tells me, which “began an exploration of another world” containing creatures he refers to as ‘biomals’. Their shape is biological, he explains, “and they’re influenced by my knowledge of biology, but they don’t represent particular animals. I started to develop them, and from that day to this, they’ve slowly evolved. Each time a new painting occurs, they’ve evolved a little bit more. Just as in real life there are evolutionary rules – you have to be able to move, sleep, walk, talk, fight, feed, eat and mate – my biomals also have their own rules, but I don’t know how I know them. If I’m painting a figure and it starts to go wrong, I know it’s going wrong and I scrap it, but I don’t know how I know it’s going wrong. It’s a very strange process, I don’t understand it, I never will.

“I’ve always been telling people I’m the last living surrealist,” he says. “I’ve now discovered there’s one in Portugal, aged 98, ruining my claim. When I say ‘last living surrealist’, obviously there are younger surrealists, but I mean people who were active when it was an active art period – back in the forties.” I wonder whether his paintings, and the genre he practiced, were ever looked down upon. “Oh Lord, yes.” After his first exhibition in 1948, “there were letters to the local newspaper demanding that all my work be burnt in a furnace. That was the kind of review I got. In those days it was absolutely loathed, we were all hated – I mean all the surrealists. Today Picasso’s almost looked upon as an Old Master, but when I was young, he was looked upon as a total lunatic. People thought he was completely mad; literally, not metaphorically – actually insane.”

In 1945 the V&A put on a Picasso and Matisse exhibition attended by a teenaged Morris. “It blew me away. Picasso’s paintings that he’d done during the war were pretty brutal, extraordinary, powerful. I remember coming away thinking, ‘How can anybody do that?’ Of course, everybody said it was disgusting and horrible. In those days everybody hated my kind of painting.”

Therefore, what made him “so determined to do it”? After all, nobody encouraged him. I suggest maybe that’s what inspired him. “Well, I think it was a sort of teenage rebellion in a way, but it was a creative rebellion. I didn’t want to smash windows, but I was pretty angry about the war.” As a kid, he was told “that ‘when you grow up, you must kill nasty people – that’s what grownups do.’ I always remember, in school assembly each morning, they’d read out the names of last year’s sixth formers who’d just been shot down the day before in their Spitfires and Hurricanes. I thought, ‘When I get to sixth form, I’ll be shot down too.’ That was the kind of life a child was living then.” At his home there was “a reinforced metal cage under the kitchen table”, which he knew to shelter in when bombs threatened. Thus, “I had a pretty dim view about adult life – I thought adults were crazy. I had to find some way of rebelling.”

After World War II, he was doing with paint what the Dadaists and other Surrealists had done following WWI: rebelling “against the horror of war” and “the adult culture of the time”. Throughout his childhood he also watched his father die from WWI injuries, “this very strong character succumbing to the wounds he’d received. He died in 1942, when I was 14. So, I was pretty angry about the establishment. I’m not an activist, I’m not a campaigner, but I have kept outside the establishment. I view politicians and people who run society with a somewhat jaundiced view, having grown up in that sort of world, and I’ve never really lost that. I’ve not become a great rebel in any other way – my rebellion remains on canvas.”

Oddly though, the thing at the core of his rebellion was littered with protocol. “When the surrealist movement was active, there were all sorts of strange rules and regulations.” He talks of Henry Moore, “a major part of the group in this country”. In need of money though, Moore created a Madonna and Child statue for St Matthew’s Church in Northampton. As the surrealist movement was against religion, he was expelled from it. “I said to him, ‘Did that upset you?’ He said, ‘Oh no, I don’t mind.’ And of course he went on to become the greatest sculptor of the 20th century. It was ridiculous of them to expel him but that was the sort of nonsense that went on.”

His own arguments with the authoritative voices of surrealism were endless. “I wouldn’t accept their politics, they were intensely left-wing, and I said, ‘No, I’m sorry, I’m not interested in politics, left or right.’” He was told he had to be politically active, but he’s never been so. While he did once vote for the Monster Raving Loony Party when led by Screaming Lord Sutch, “I’m just not interested in politics at all. It’s important, like road-sweeping and refuse collection, but it needs to get on and do its job and not make a nuisance of itself.”

The surrealist rules were imposed by André Breton, the “contradictory behaviour” of whom Morris wrote about in The Lives of the Surrealists. “How can you have rules and regulations for a movement that is essentially irrational? He wanted surrealism to be communal, he said individuality must go. And there were people like Dali and Max Ernst – highly individual. Dali was expelled, Ernst was expelled twice I think, most surrealists were expelled from the movement and then usually taken back later because they were too important to be ignored.” Despite his pettiness, though, Breton “gave impetus to the movement. I made a bit of fun of him in my book; at the same time I did explain that he was crucially important – he gave it gravitas.”

The Lives of the Surrealists was published last year. He wrote it because he knew the likes of Moore (“I was very fond of Henry”), Francis Bacon, Alexander Calder and Barbara Hepworth. “I thought, ‘There’s nobody left really who knew these people.’ I have anecdotes about them; I didn’t want to waste that knowledge.” The book’s been a success, translating into lots of languages – “They’ve just done a Russian edition which pleased me.” He has another book being published by Thames & Hudson in the autumn, Postures: Body Language in Art, for which he’s “gone back through the history of art and looked at the way in which portraiture portrays people”.

Since finishing Postures he’s been painting for the exhibition. He splits his year into two halves, writing for one and painting for the other. “We live in an age of specialisation,” he says. “People become fixed in one particular career, and then they have a few pastimes.” But he has “two main activities” that he bounces back and forth between. “When I’ve finished a book, I don’t want to do another. I don’t know how authors who write book after book after book can do it. When I’ve painted a series of 50 pictures, and had an exhibition, that part of me is exhausted. I don’t want to paint any more pictures. Picasso painted every day of his life, I couldn’t do that.”

In the 1940s, he would exhibit artwork in Wiltshire, but couldn’t sell it. So he began studying another passion, animals, going on to be a professional zoologist. This earned him a lengthy television career which saw him make about 700 programmes. When he reached his eighties he stepped away from TV, and from giving lectures – something he used to do all around the globe. This allowed more time to write and paint, and in 2017 he did more paintings than any other year of his life. “I’ve actually painted more pictures in the 21st century than I did in the whole of the 20th.”

He works at night, “I’m fairly nocturnal.” A few years back he would keep going until 4am. “Now I’m going to bed earlier, two o’clock, three o’clock – early for me.” He’s always been this way. “Every individual has a 24-hour rhythm in their brain, and there are larks and there are owls.” He had a lark for a professor, who would rise at 5am and get all his writing done by 8am. “In the evening you could see him going downhill. With me, it’s the exact opposite; my brain gets better and better as the night goes on – by one o’clock I’m buzzing. The larks always feel superior to the owls,” he resumes, “I don’t know why, people who get up early always feel superior to those who get up late. I’m afraid I’m stuck with being an owl, it’s something to do with brain processing. I couldn’t work in the morning, it takes me several hours to come to, whereas my professor couldn’t work at night. Most people are in the middle, but there are people at the two extreme ends. It’s ok, it’s not a problem.”

Does he pity today’s young people in any way? “What you’re talking about, I suppose, is the technical period where everybody’s on social media and all that sort of thing. When I’m asked about the social damage done by the mobile phone and the computer, I always say they’re tools you can use, and as long as you use them as valuable tools, they’re tremendously important. They provide you with huge amounts of information and communication. But if you become addicted to them, then they use you, and you suddenly give them preference over ordinary social living – when that happens, you’re in trouble.”

Addiction puzzles him more than anything else, says the behaviour student. “I’ve had close friends, lovely people, who’ve killed themselves through booze. Gerald Durrell was an old friend of mine, and he knew he was killing himself. He had to have a liver transplant, for God’s sake, and he still didn’t stop drinking after. I thought, ‘Gerry, why?’ But you couldn’t argue with him, he just couldn’t stop. I don’t understand that because he was an incredibly intelligent man – a lovely man, one of the funniest men I knew – and he was killing himself with booze. How can an intelligent brain allow that?” He was a smoker back when “everybody smoked” but quit in about 1980. “It was starting to affect my lungs so I stopped.” How? “I didn’t smoke anymore – it didn’t seem to me to be a big issue. I had a friend who was still puffing away. He said, ‘I can’t stop.’ Just don’t light a cigarette. He said, ‘I can’t help it.’ Most of the time, if something’s damaging, we don’t do it. But with addiction, that rule goes out the window. If you’re a smoker or a boozer, your intelligence just doesn’t seem to switch on. I’ve never been addictive, I love booze but I only drink a little, I don’t let it use me.”

The conversation soon turns to “cranky diets” that exist today. “We are omnivores,” he says, “we evolved as omnivores, and the healthiest diet is one that is as varied as possible – that’s what omnivore means. You don’t need dietitians to tell you what to do, you just eat a variety of food and you’re ok.” If you’re an adult partaking in quirky food regimes, he says, then that’s “your own silly fault”. To force them onto children, he believes, is cruel. He’s “never taken the slightest bit of notice” of slimming books either, “because to me it’s very simple: if you’re too fat, you eat less; if you’re too thin, you eat more. You could just publish that as a diet book, that’s all you need.”

As with others I’ve spoken to for this issue, I bring up the Best of British theme, seeing if he can shed any light on what it means to be British at the moment. He recalls the sentiments of “an old chum”, Spike Milligan, who would tell him “the great thing about the British is that they relish their eccentrics. We don’t,” he elaborates, “have the sort of culture that eliminates behavioural variety, we actually encourage it, there’s a freedom of behaviour which I think is special to this country.” Seventy years ago, people may have said his paintings should be burnt, but they didn’t actually do it, “which is what some countries have done in the past with artists. We can argue about things, and attack things, and criticise things, but in the end we are given much more individual freedom in this country than you find in many others. That’s what being British is about to me: freedom of expression. We have to be very careful we don’t lose that. It’s what has led to so many creative British people, in many different spheres; British comedy has always been superb compared with other countries, British music has been incredibly original – and rebellious. We have a great track record of being a rebellious nation, but in a non-destructive way. That’s what I like about the British.”

Could he ever just stop creating? “Good Lord, no.” He’s obsessed with writing books and painting pictures. “I wish I were musical. I envy people who are creative musically, I just can’t do it. I love music but I cannot invent music. But you know,” the artist, writer and owl points out, “you can’t do everything.”

Bodyworks: The Art of Desmond Morris takes place at Mallams Auctioneers, Oxford

4 April, private view

5-7 April, public viewing