It was a sunny midnight in July as I wrestled my kayak over the ice shelf that hugged every inch of this windswept shoreline like an Elizabethan collar. Low tide had left an overhanging blue-white wall ten feet high, dripping and dangerous. As I tried to heave myself over it, a block of ice the size of a small car cracked off nearby and crashed into the sea, sending a huge wave hurtling towards me. I quickly clawed my way over the side, for I was here on a mission in search of long-lost ghosts and didn’t want to join the Casper fraternity.

A fatal step at this spot wouldn’t have been the first. This barren shore, just off Ellesmere Island in the tortured topography of Canada’s High Arctic, was the scene of one of the worst disasters in the history of Arctic exploration.

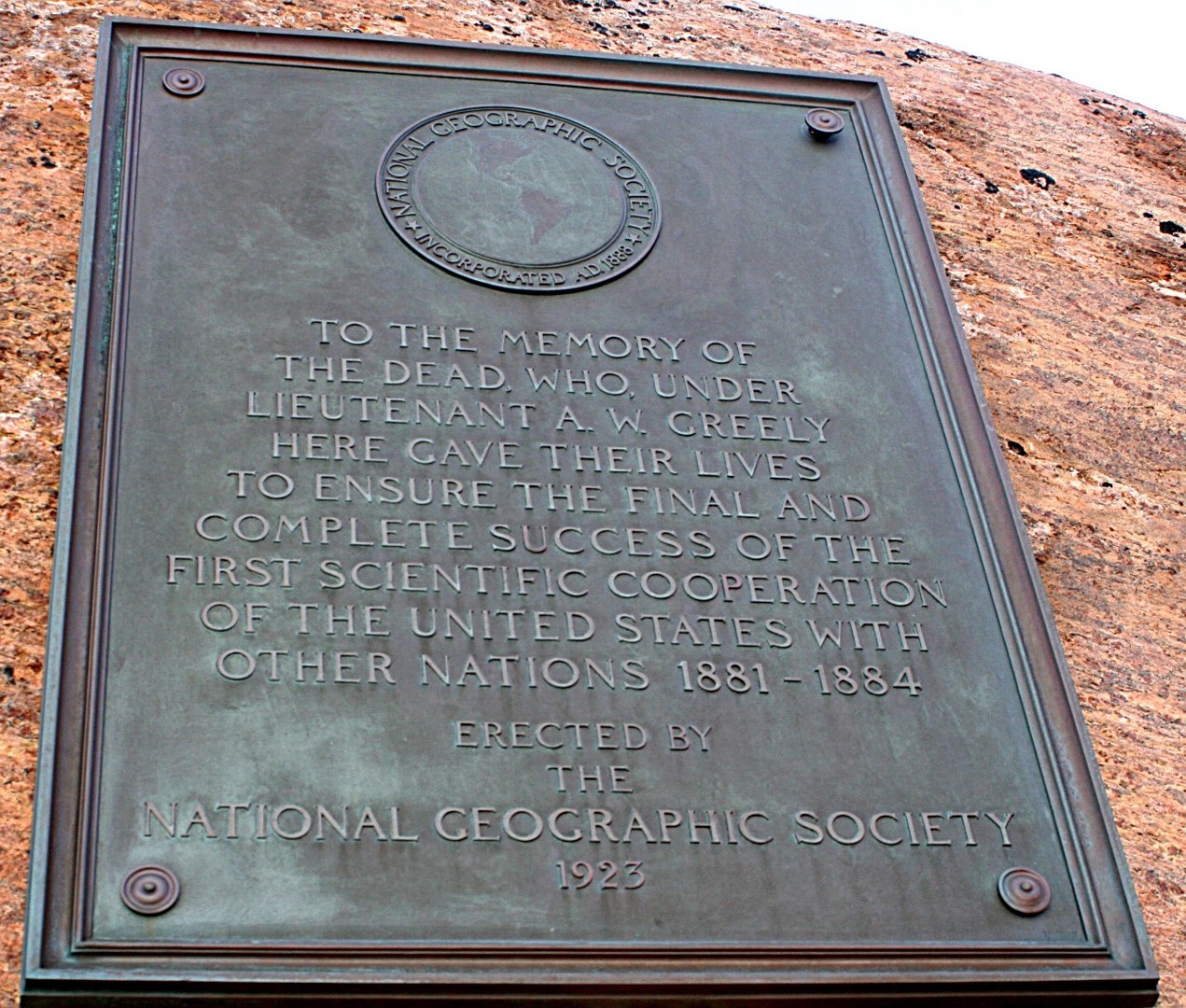

In the season of 1881-1884, the United States Army officer and explorer Adolphus W.Greely led an ill-fated expediion to northern Ellesmere Island as part of the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition on the ship ‘Proteus’. Its purpose was to establish one of a chain of meteorological observation stations as part of the inaugural International Polar Year (IPY), which was a collaboration of international efforts to focus intensive research into the science and meteorology of polar regions. The secondary goal of the expedition was to search for any evidence of the ‘USS Jeannette’, lost in the Arctic two years earlier.

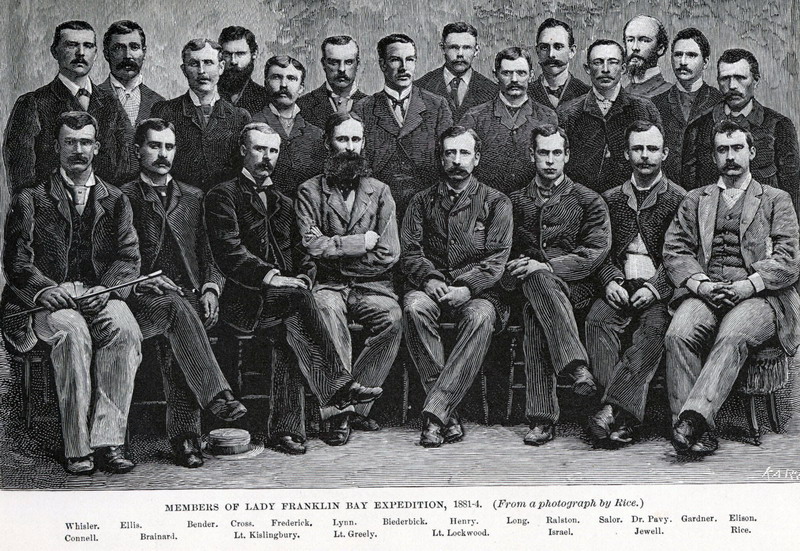

Lieutenant Greely and his crew of 24 men, including the astronomer Edward Israel and Canadian-born photographer George W. Rice were without previous Arctic experience, but he and his party were able to discover many hitherto unknown stretches of coastline along Baffin Island and the northwest coast of Greenland.

The ‘Proteus’ arrived at Lady Franklin Bay on 11 August 1881, dropped off men and provisions, and over the coming months, set up their first meteorological observation station overlooking the Nares Strait, a narrow waterway between Ellesmere Island and Greenland that connects the northern part of Baffin Bay with the Lincoln Sea.

Over the next nine months, the conditions at Lady Franklin Bay worsened by the day and Greely and his crew ended up stranded. ‘Proteus’ had been crushed by the ice and they spent seven terrible months under an overturned boat, trying to survive on a small emergency cache with 40 days’ worth of rations which had been dropped at Cape Sabine on the outward voyage. By the time a relief ship had arrived, all but seven of the men had starved to death. The rest had succumbed to hypothermia, drowning, scurvy and suicide, and one poor soul, Private Charles B. Henry, had been shot on Greely’s orders for the repeated theft of food rations.

Members of the ill-fated Lady Franklin Bay Expedition (1881-1884), prior to embarking for Ellesmere Island in 1881. Lieutenant Adolphus W. Greely is pictured here in the front row, fourth from the left. Sitting to Greely’s right, his second in command, Englishman, Lieutenant Frederick Kislingbury.

The bodies of the dead were returned to their families in sealed caskets with instructions not to open them. Rumours soon began to circulate about exactly how these men managed to survive without food for so long.

There were even accusations of cannibalism among the crew following the return of the bodies. On the morning of 14 August 1884, a few days after his funeral in Rochester, New York, the body of the Englishman, Lieutenant Frederick Kislingbury, who was born in the village of East Ilsley, Berkshire, and second in command of the expedition, was exhumed from his modest grave at Mount Hope Cemetery and an autopsy was performed. The finding that flesh had been cut from the bones of his ravaged remains appeared to confirm the desperate and tragic lengths to which the survivors stooped to prolong their lives in the hope of rescue, which Lieutenant Greely strenuously denied.

It was a chance discovery of Lieutenant Kislingbury’s lamentable obituary in the newspaper archives of The Travellers Club in London, that first inspired me to return to this unforgiving, hostile region of the High Arctic, a vision that was finally fulfilled in the spring of 2018.

There are only three settlements on the island, Alert (population 64), the Inuit hamlet of Grise Fjord, seen here from the north, which is the largest community on the island (population 129), and the small research base at Eureka, home to a temporary population, and one deserted military base.

I had sled-hauled and kayaked for two 10-hour days to get to this icy outpost on Pim Island, which, along with neighbouring Ellesmere Island, forms part of the Queen Elizabeth Islands group. I was hungry but too excited to eat. Besides, it didn’t seem right to explore Greely’s historic ‘Starvation Camp’ on a full stomach. Parking the kayak beside some fresh polar bear droppings, I scanned the rocks for the low stone wall that had sheltered Greely’s boat. And then I saw it, a few steps from the shore, three to four feet high. The interior of the ‘hut’ was bigger than I’d expected – the boat had been no mere car-topper. Like most historical places on Ellesmere, the remains of the camp were as undisturbed as if the occupants had huddled there this morning.

Here in this dry, polar desert it takes centuries for man-made creations to return to their natural state. Dozens of rusted tin cans, whose 19th century contents had been apportioned so carefully, were scattered about the ground. Inside the enclosure lay tatters of the white sailcloth that had covered the boat. There were also the remains of some woollen garments, one with a button still attached.

Greely and his men had been on a mission to explore the coasts of Greenland and Ellesmere when a supply ship, the ‘Neptune’ scheduled to pick them up never arrived – it had sunk in heavy seas. Two months later another rescue attempt fell through, leaving the stranded men to face the full force of the Ellesmere winter. Besides the cold and lack of food, they had to survive a location that left them exposed to the rampages of weather generated in Baffin Bay, one of the most dangerous bodies of water in the world.

Fortunately, my own expedition to the region was made considerably easy by comparison, for it was my good fortune to be hosted part of the way as a passenger onboard the ‘Ocean Endeavour’, one of the new breed of ice-strengthened expedition cruise ships that now sail from Kangerlussuaq in western Greenland to the old copper mining hamlet of Kugluktuk, the westernmost community in Nunavut, cruising into the very heart of the notorious Northwest Passage.

Baffin Bay is so stormy that it never freezes, despite four months of darkness and average winter temperatures of 30 degrees below zero. Everywhere around its periphery, the sea ice reaches eight feet thick.

It gets thicker than on land, with one third of Ellesmere covered by ice caps and glaciers. But there are also surprising chunks of this mountainous fjord-cut land that are not year-round freezers, and which are home to an abundance of flora and fauna.

The wildlife of Nunavut has drawn intrepid two-legged visitors, too, over the years. On nearly every rocky outcrop you can find tent rings, fox traps, whale vertebrae and other ancient artefacts left by the Inuit hunters who have wandered throughout the High Arctic for the past 4,000 years. Signs of more recent arrivals are also abundant in this open-air time capsule. Cairns from the first explorers of the region are everywhere. If you’re lucky enough, you may even find a box of Sir John Franklin’s supplies cached away in some little valley, or the remnants of Robert Peary’s controversial 1898-1902 expedition, such as old wooden sailing blocks and tackle pulleys, one of which now takes pride of place in my study.

Ellesmere is as large as Britain, though it comes with fewer roundabouts and motorway junctions. There are only three settlements on the island, Alert (population 64), the Inuit hamlet of Grise Fjord, which is the largest community on the island (population 129), and the small research base at Eureka, home to a temporary population, and one deserted military base, a former Cold War listening post on the Ward Hunt ice shelf.

Like most worthwhile places to visit, Ellesmere is hard to get to. There are no commercial flights, so you need to either join a tour, have fabulously deep pockets or else practice the once hallowed but now disreputable arctic tradition of bumming a ride on an aircraft, which is what I usually do. Some years it’s easy; others it’s so humiliating that I lose all desire to go to Ellesmere for a while, until the ghosts of those early explorers clanking their chains start calling me back.

Then there are the professional adventurers – the archaeologists, geologists and botanists who come to track prehistoric settlers. John England, a, geologist from Edmonton, Alberta, has put in 15 fieldtrips on Ellesmere. His first season was so magical – great weather, field results, and the bonus of many discoveries – that he and his partner, Helena, debated hiding when the plane came to take them home.

To sail through the Northwest Passage is to sail through living history and the rich, cultural heritage of the Inuit who have called this remarkable place their home for countless generations.

Thanks largely to the work of Peter Schledermann, an archaeologist with the Arctic Institute of North America, located in the University of Calgary, whom I met during my visit, the area around Alexandra Fjord has become renowned for its Thule Eskimo ruins. The most famous, on Skraeling Island, has also yielded Viking artefacts, including chain mail and woollen cloth of Norse weave that has been carbon-dated to 1250 AD. If the Vikings had gone the same distance south, they would have received chain mail burns in the Caribbean. This place is so far north that Hudson Bay is practically equatorial, 900 miles to the south.

The ice was still thick in Alexandra Fjord when I hauled my kayak on a little homemade ‘komatik’, or wooden sled, to Skraeling Island. The kayak let me cross the shore lead – the moat of water between land and ice that forms in early summer. Sea ice breaks up differently than freshwater ice. By late June it’s a jigsaw of solid ice and shin-deep meltwater pools. It’s scary at first to walk through those pools – you become convinced you’re going to break through. But despite appearances, the ice beneath is solid. The only thing you have to avoid are the seal holes that gape like open manholes, and the polar bears that frequent them.

In the milder climes of Skraeling I found a grass meadow that had been home to Thule hunters 700 years ago. I peeked into the crevices of their stone walls and lay on raised sleeping platforms, which were much too short, even for me. The whalebone stays that supported the stone and sod roofs were long gone. Bowhead whale vertebrae, as big as Spitfire propellers, lay on the ground or were integrated into the structure of the ruins.

My last stop on this part of Ellesmere would take me to the abandoned Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) outpost on nearby Bache Peninsula. In the 1920s and early 1930s it was the starting point of some of the longest sled journeys ever undertaken, trips that spanned up to 1,300 miles by Sergeant Major Henry W. Stallworthy and Inspector Alfred Herbert Joy, and their courageous Inuit sled master Nookapingwa, as part of the now legendary Oxford University Ellesmere Land Expedition.

The author is pictured here kayaking among the ice flows in Alexandra Fjord, a breath-taking inlet on the Johan Peninsula of Ellesmere Island. Peter Holthusen has often travelled along the routes of those early Arctic explorers, more often than not in search of some of the ancient Inuit settlements that can be found there.

Strong winds had opened the sea ice, and I was able to kayak 15 miles to Bache. Along the way, black guillemots orbited curiously around me. Four narwhals, 20-foot whale-like cetaceans with spiral tusks, came within 10 yards of my kayak before they spotted me and sank from view, leaving a glassy slick on the water.

The Bache buildings themselves had been dismantled or transported by dog teams to the newer outpost at Alexandra Fjord in the 1950s, but plenty of eloquent detritus from that earlier, golden age of the RCMP remained – one wooden crate of dog food, another of Christie’s biscuits, and even a box of paperbacks that had helped the Mounties through Ellesmere’s four-month-long dark season. Considering that the books had sat outside for seven decades, they were in remarkably good shape. Most were not Jack London fare but romance novels of the day. One chapter began: “The loveliest mouth in France turned into a distracting smile.” The toughest ice dogs in the Mounties were also some of the loneliest of lonely hearts.

On the eight-hour trip back from the Bache Peninsula the next day, I took a stretch break on a little island in the middle of Buchanan Bay. It was high tide, so I was able to exit the kayak easily and slip it onto the ice collar. Orange lichen brightened the rocks, and a nesting Eider duck sat close to her brood. There was one tiny meadow, maybe 10 yards across. In it were the ruins of a Thule house, no doubt undocumented, with a couple of whalebones embedded in the soft moss. I sat in the ancient home for a while, enjoying the sun, with nothing but rock and sea around me to eternity. But the solitude wasn’t quite complete. As elsewhere on Ellesmere, I sensed company. Next to me, I felt the presence of an ancient Thule hunter, tough and weathered, scanning the horizon of this unforgiving wilderness, joining the ranks of the fearless adventurers who have been lured by its spirit and legend.