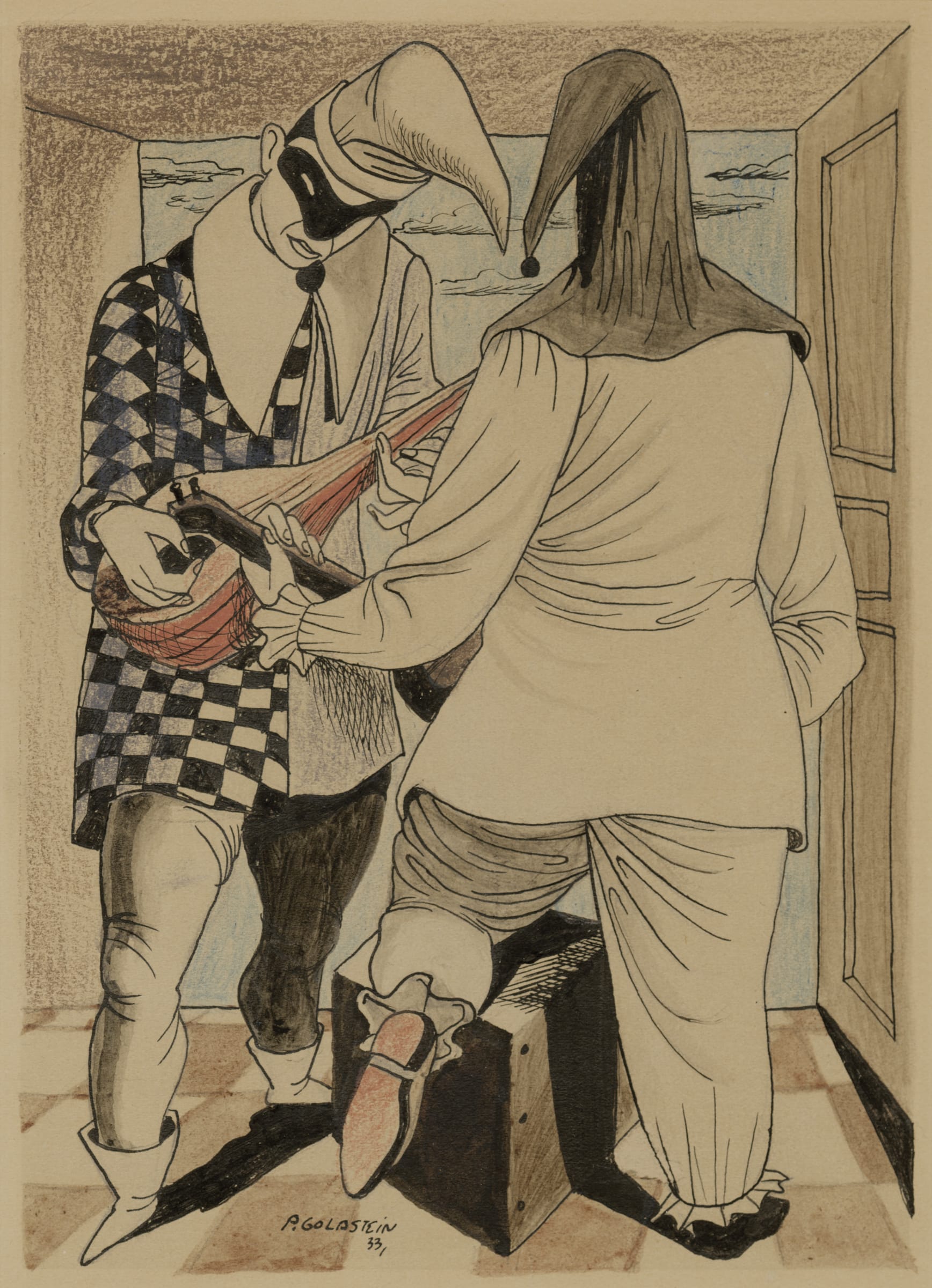

“In the small room of the world-infested head,” writes poet Louise Larchbourne, “two strangers touch each other.” She is describing artist Philip Guston’s 1933 ‘Punchinello Drawing’, in which two comical figures stand playing music in an enclosed space. But like every good poet, Larchbourne is talking about two things at once. “Today,” she reflects, “every head is world-infested, with a never-ending reel of global information. The only remedy to this affliction lies in slowing down and using art to make real personal connections.”

This is the sentiment behind Poetry in the Galleries, a recurring event in the Ashmolean which features work by Oxfordshire poets in response to a given collection from the museum. Each gathering explores a new exhibition, a new theme, resulting in a brand new slate of poems presented beside the piece of art which inspired them. Larchbourne was just one of six poets responding to Philip Guston: Locating the Image in Saturday’s event. It feels like the meeting of a secret club of poetry and art enthusiasts, dedicated to mining with words for the hidden gold behind every display. Taking place sporadically since 2012 and now growing into a steady rhythm, Poetry in the Galleries has been right under our noses for years – an overlooked gathering weaving through exhibitions with nothing but humble words and handfuls of paper. Yet, for all the event’s informality and unceremonious packaging, the poetry itself glows. Battling the echoes of the surrounding museum, quiet, poignant words reach out and shake the whole building so that all within it might stop and listen.

This is the best way to experience a collection. The museum is already a place of contemplation – indeed, when entering the Ashmolean’s maze of galleries, every direction gives way to murmured discussions, intrigued tour groups, or the silent gaze of individual reflection. But poetry takes all this palpable wonder from the space and transforms it into its own complementary medium – the language of wonder beside the very works that provoke it, to be considered in tandem. Words intertwine with the art so thoroughly that one seems incomplete without the other; Larchbourne writes of one ink-drawn figure, “He’s what ‘aghast’ was named for”, as if the word now belongs solely to Guston’s art forevermore.

Eager to admit that they too had no idea what the works of art really mean (a relief to this habitually perplexed art admirer), the poets instead found value in vivid descriptions of what they could mean, or in the wealth of personal memory that they stirred. Sarianne Durie’s language was full of ambiguity – all perhapses and possiblys and mights – while Teresa Hewesufa Bencinic eloquently filled the blank space beneath two dark inked eyebrows (Guston’s ‘Aloft’) with the memory of her mother’s eyes.

In a museum like the Ashmolean, the sheer quantity of treasures between its walls can overwhelm. Too often do we see a mere generalised collection without looking closely at anything in particular. But these poets offer a new way of looking. Individual displays are selected, scrutinised and explored with probing language to the very corners of their strangeness. It is the kind of experience that raises many questions and answers very few; but here, answers are superfluous. Instead, all focus is on the conversations these questions spark – and the resulting connections forged between museum-going strangers.

The next free Poetry in the Galleries event is at the Ashmolean on Saturday 21 March, 2-3pm.