I always said that if my mother ended up demented or decrepit and needing someone to take care of her, she could count me out. I was adamant that I was never going to sacrifice myself again for her needs. I know this sounds harsh. But I was young and angry.

‘It’s time for me now,’ My mother would so often say when we needed her. ‘I’m putting myself first for a change.’ But the truth was that she’d always put herself first. It’s just when someone, especially a parent, tells you otherwise you tend to believe them. We thought we demanded too much, that we were selfish and unreasonable, when all we craved was the bare minimum.

I’d been estranged from my mother for well over a decade. And from my sister for just as long. So when the message came, I was blindsided.

Just thought I should let you know. Mum’s not good. Frail, confused… terrified of doctors. She’s a tiny little old lady now, Sammy.

We arranged a phone call.

It was strange hearing my sister’s voice after so long. Sad, comforting, familiar. I realised I missed her so much my chest ached with longing. I was more interested in hearing about her than about my difficult mother. In fact, so many emotions and memories flooded my head I felt dizzy with them. I wanted to cry and scream, but I also felt numb.

My mother was living alone, in the ramshackle flat above a dry cleaners where we’d grown up. A woman who had been so beautiful and vibrant, with so many lovers and people in her life. Now she was only visited by Kevin, her long-standing best friend, once a week who brought with him a supply of fizzy water, coleslaw and chocolate biscuits: the sole things she would eat.

I agreed to go around and assess the situation. My sister lived at the other end of the country and Kevin was out of his depth. I was only a ten-minute drive away. Now I knew what was going on, I didn’t have it in me to turn away. I had to do the right thing, otherwise I’d be as selfish as she’d always been.

Her front door was wide open. It was the week before Christmas and there’d been a cold snap. Ancient leaves danced on an icy wind at the threshold. I paused for a moment, uncertain at what I might find. Then I entered, cautiously, holding a pot plant, a bumper pack of digestives and a bottle of mineral water.

The stairs up into the gloom of her flat were steep and moth eaten. Dust covered everything.

‘Hello?’ I called. ‘Hello?’

A shadow peered over the landing banister.

‘… who’s there?’ A wavering voice wafted down to me.

‘It’s me, Sammy – your daughter’

There was a scuffling, and slowly a strange creature appeared at the top of the stairs. She was like a character from a fairy tale. Arthur Rackham or Dr Seuss. One shoe on, one shoe off. Stripey leggings. A strange bobble hat and a fake fur coat.

‘My Sammy?’ She enquired shakily. ‘Is it really you? I have so many dreams, I’m not sure what’s real…’

She hugged herself and bounced on the step like a child. I could see the glint of her blue eyes, and the long white hair which fell past her shoulders. She was Miss Haversham, and someone had finally come to call.

‘Yes, its me.’ And then it left my mouth before I knew I was going to say; ‘I love you…’

And as I said it I knew it to be true. Despite everything.

‘Thank you. Thank you, God.’ She whispered. ‘How I prayed for this day.’

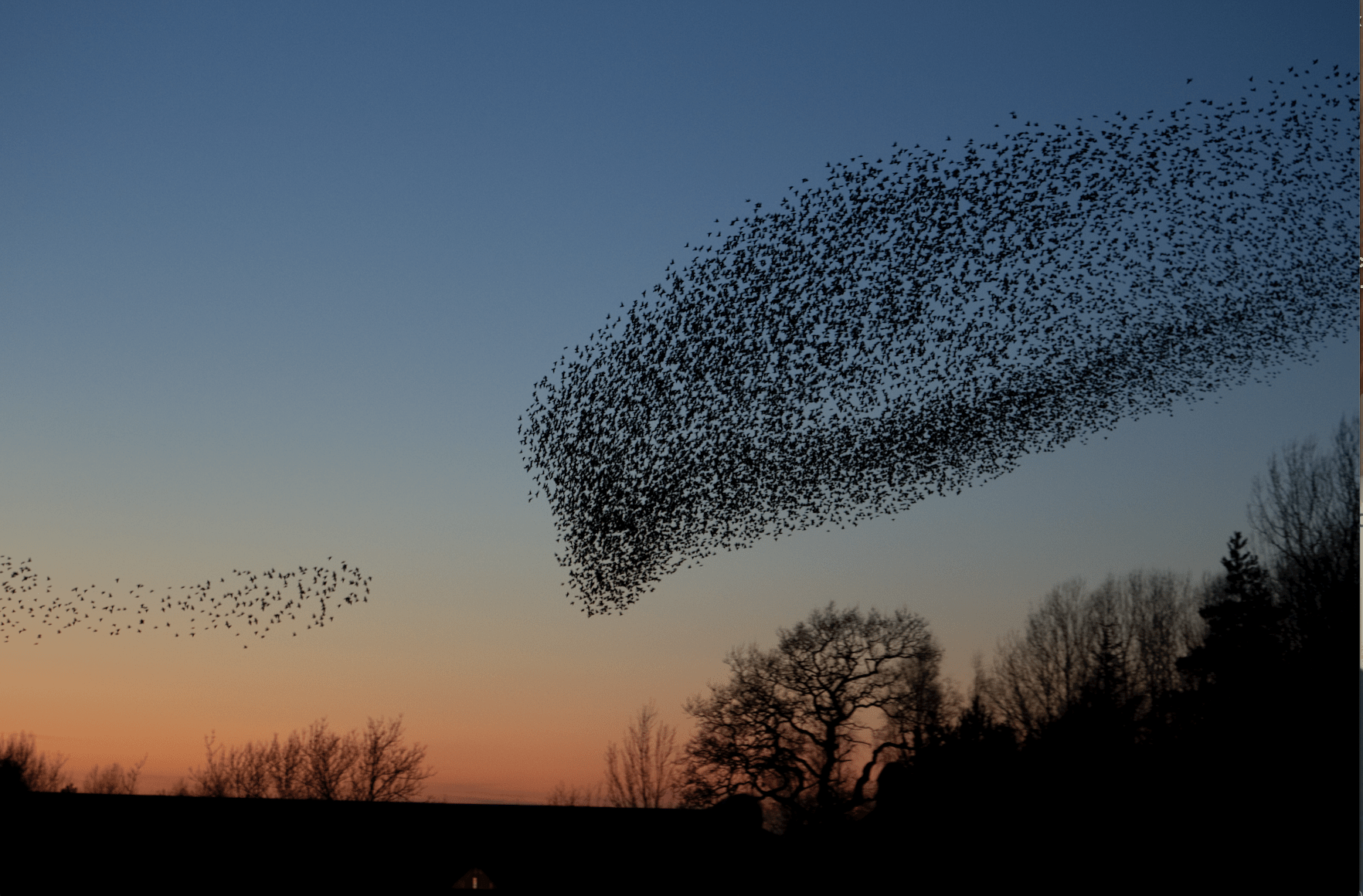

Then she inched down the stairs in her bizarre get-up. Tiny, so tiny with bird-like hands fluttering ahead of her as she felt her way. When she reached the bottom, I stepped forward and embraced her. I felt her frail bones and bowed back that had once been so upright and defiant.

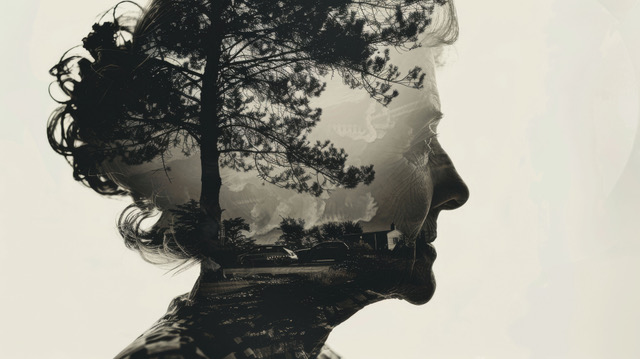

My Mother

My Mother

It became quickly apparent that she had advanced dementia and osteoporosis. She’d been working until a couple of years prior, making up gifts at a local garden centre, so the onset had clearly been rapid. Lying in wait until she became idle.

To stand, sit or walk caused excruciating pain. She winced at loud sounds and found daylight so painful that all the curtains were drawn. She had a timid little white cat who cowered in a corner. Trinkets and keepsakes littered every surface. And half eaten chocolate biscuits.

She spoke about the past: difficult memories of her father, regrets that she wasn’t running a cat shelter as she had wanted to when she retired. Then she slipped into reveries about past lovers I could have done without, and confused recollections about arguments and fallings out with me, my sister and other people, both real and – as I came to understand – imaginary.

She had vivid hallucinations and delusions. She saw cats, dogs, ducks, bats. She had conversations with a large invisible woman called Hannah who reprimanded her for eating too many biscuits. She’d been kidnapped by a cult, appeared on a gameshow, had a battle with a man who lived on the roof and thew excrement at the window. (All untrue.)

She always said that she wasn’t hungry, but was ravenous and wolfed down a supper of cheese pie that I brought round and heated in the microwave. ‘Be careful’ she’d warned, eyeing the microwave suspiciously…‘Kevin nearly blew it up’. (He’d told me she’d left a fork in there and also often left the gas on).

I called social services who promised a visit to assess as soon as the holidays were over, and we managed a trip to the lovely local GP who performed a memory test and took bloods and vitals. ‘It’s probably Lewy body by the looks of it,’ she ventured. ‘It’s hard to be sure without proper investigations, but it seems very florid and she has the Parkinsonian tremor indicative of it…’

I committed to visiting her a couple of times a day until we could get the ball rolling with social and health care in the new year. I took her hot food and talked to her, or we watched TV together. She often thought events on the TV were real, and she would often fall asleep mid-sentence. But when the day darkened towards evening, she suddenly became more active. Rushing about the flat despite her disability, moving objects, talking nineteen to the dozen, to herself or others only she could see. Sometimes she became antagonistic, and her conversation dissolved into a world salad. Sundowning they call it.

It was on New Years Day that I got a call from the police. It had snowed and she’d decided to go out for a walk. She’d fallen and had lain in the snow for a long while before a dog walker found her. She had no shoes on, and no coat.

She was rushed to hospital with a hip fracture and hypothermia. She was screaming incoherently when I got to A&E. She’d gone out looking for the portal back to her real world, she told me. Because this was not the real world. And I wasn’t really me. I was ‘the other one’.

Then she got angry and how I remembered she could be. How scared we were of her. How she would pit us against each other. How she would hurt us.

They wheeled her off to emergency surgery shouting obscenities. I sank down into a hideous orange chair as the emergency ward sister came over and gave me a hug. ‘Don’t judge me … I didn’t know how she was. We, we had a very difficult family dynamic.’ I didn’t go into the fights and abuse: the tears and the stolen boyfriends. ‘We don’t judge here,’ she replied handing me a tissue. ‘I haven’t spoken to my family since I came out and left home. Families are difficult …’

I found myself hoping that she would slip away under anaesthetic. And was ashamed of myself. My sister said something similar when I phoned her to tell her what happened: ‘I just wish she’d go to sleep, you know? Forever. Isn’t that awful?’

‘I’m sorry’, I told her. ‘I’m sorry I wasn’t a better sister’. ‘You never did anything to stop me from loving you. Never ever,’ she told me. ‘And when I sent you that message, Sammy, I knew you would step in and do the right thing. And you have – you always did.’

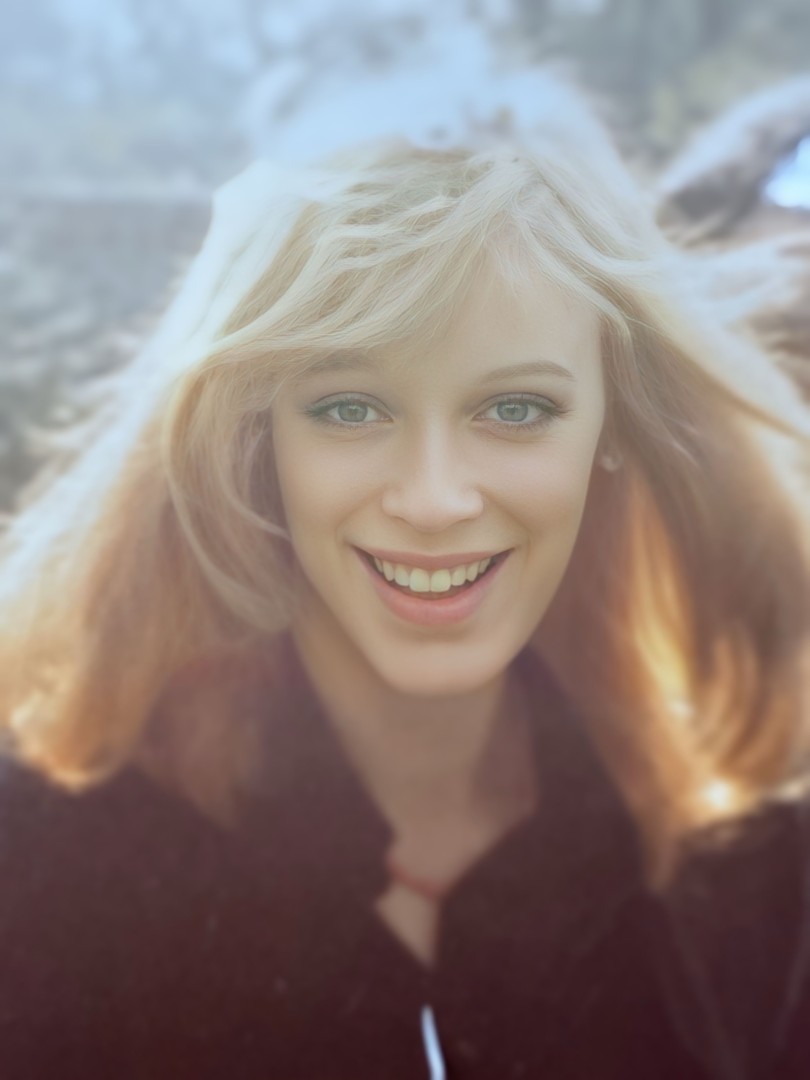

When we’d met after all that time to visit our mother after her surgery, my sister was exactly as I remembered her. Beautiful of face and spirit. Kind. Understanding. My mother’s blue eyes. I dissolved into tears, and she brushed them away. ‘None of that,’ she said. ‘It’s okay. We’ve got each other back. I’m not going anywhere.’

‘Neither am I.’ I sobbed and blew my nose loudly. Then we laughed at the absurd noise and couldn’t stop. It was relief and a kind of wild hysteria, but it was because we couldn’t believe this day had come for us to be together again.

Thankfully hospitals can’t send a vulnerable person home if they can no longer look after themselves. My mother recovered from her surgery but descended further into physical and mental frailty. She would often not recognise me at all, but think I was a nurse or a doctor or someone else altogether.

She’d long ago blown any money she’d had, living off her pension and relying on housing benefit. A kind, achingly young, social worker found a place in a care home paid for by the state where my mother could have her things around her and a garden to look out at. She told me the elderly with dementia love soft toys and so I bought her a soft furry lynx she is seldom without. She has kind people from faraway places who care for her. She doesn’t have long, they say, and she is sort of young to be in such decline.

I’m grateful, though. Grateful that when the call came, I found it within myself to do the right thing by her. Grateful she is now safe and looked after. Grateful I got to tell her I loved her, whilst she could still understand what I was saying. Grateful because I remembered that she could sometimes be the best person ever, that she taught us about books and art and made us laugh. But above all I’m grateful to have my sister back in my life because we make each other whole.

Useful information for those affected by issues raised in this piece:

oxfordshire.gov.uk / 0345 050 7666

Sam Faith is writer and filmmaker. Find her on Instagram @IamSamFaith