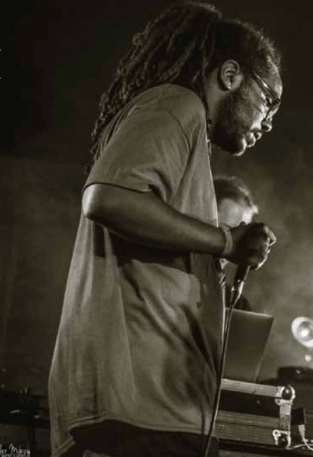

Rory Campbell, AKA Rawz, speaks to me fresh from meetings in Oxford, “really positive and exciting stuff – it’s good to actually see people face-to-face as well after all these months of seclusion.” Lockdown was “a double-edged sword” for the rapper, allowing him to get in touch with his creative self at the same time as separating him from colleagues at Inner Peace Records. “Being in a physical environment with other artists is a really inspiring thing for me,” he says, “so I’ve missed that.”

His “day job” is at Meadowbrook College, an alternative provision academy for students who have been excluded from, or have trouble accessing, mainstream schools. “All the work I do there is about building relationships with young people, working with them on their terms.” It’s been harder remotely, he says, “an impossible task” to glean the social cues and emotional signals he can in-person via a ten-minute phone call once a week.

It’s a lot to ask of the pupils as well, I say, for whom remote learning has meant a level of self-discipline that even grownups have difficulty reaching. “These are kids who have struggled with mainstream education and require a lot of support to get through an English or maths class – they often have their own worker who will sit with them in lessons. So, to then ask them to take it upon themselves to get up every morning, sign themselves into Google Classroom, download work and then work through it – maybe on their own or maybe with a parent who isn’t a trained educator at all – to be honest, most of my students didn’t get a lot of work done during that time.”

Positives have come out of the situation though, such as “improved relationships with parents and carers through that enforced closeness”. One student’s mum kicked them out shortly before lockdown, he tells me, so had to move in with their dad. Three months of close proximity to each other actually ameliorated their testing relationship. His Meadowbrook work is “not so much about academic achievement” as it is developing functioning adults able to form positive relationships with people. “That kid having a better relationship with his father is ten times more valuable than getting a better grade in a test.”

How did he end up in this line of work? “It’s a fairly long story,” he warns, “but I’ll tell you because we’re talking.” He was just 11 when his grandad (“one of my main male role models”) died. Then his mum and stepdad divorced following “a very dysfunctional relationship” lasting a number of years. “I was struggling at school as well,” he says, “so going through a pretty tough time from the ages of 11 to about 15.” Writing lyrics was therapeutic for him, helping him to organise his thoughts and express himself. “As I got a little older I found a few other members of the community in The Leys who were also interested in making music – lyric writing, hip-hop – and we started to put out CDs for free in our local area.”

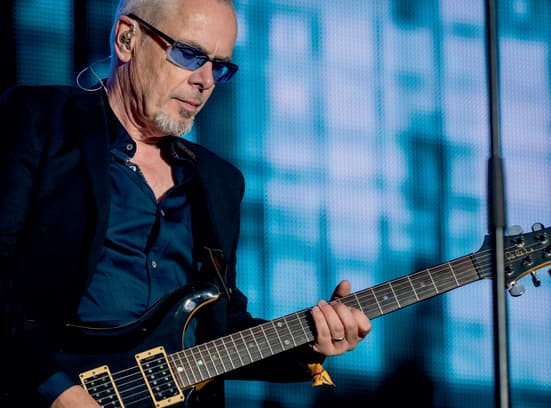

In a bid to advance as a lyricist he attended a Steve Larkin-led poetry and storytelling course on Cowley Road. Impressed with his words, Larkin asked Rawz to assist him the next time the course ran. Around that time, Leys CDI (community development initiative) requested his involvement in one of their music projects. Both ventures then ran out of funding. In 2009 he launched Urban Music Foundation, carrying out the same kind of work, before landing a role at Oxford’s Ark T Centre; a music project with Candyskins bassist Brett Gordon, who taught him how to conduct a recording session. “We ran that for a good few years – along with Hannah Bruce – and then funding again became an issue and it was becoming really difficult to support myself. By that time I had a young son as well and was kind of worried about being able to give him a stable environment.” He sought a job focused on young people and music, leading to a music teacher position at Meadowbrook and then as part of the college’s Discovery programme in Abingdon, on which he’s still an instructor. It’s effectively an intervention, he explains, for disillusioned schoolkids in years 7, 8 and 9. “We basically try and change their mindset and attitude towards working and towards authority. We help them turn that around and hopefully go back into a mainstream school – or we point them in the direction of a more specialist school.

“I said it was a long story,” he says, before I ask him about his 2014 record, The Difference, which he recorded at the aforementioned Ark T – “a really valuable space for the arts”. He can’t remember all the tracks on there, he says honestly, “but ‘Mary Lamb’ is still relevant today.” The song tells of a woman that rises at 5am every day for a job she hates, and dies one morning in a car accident. The subject remains pertinent, the songwriter points out, at a time when people are questioning the necessity of their daily commute.

The Difference’s principal theme – contrast in Oxford – is also still germane. “I was doing some work on Iffley Road at a sheltered accommodation for homeless teenagers who had some really horrendous stories, and then across the road, Magdalen College School where boys’ parents pay thousands of pounds per term.” Some of England’s most deprived young people a stone’s throw away from some of its most privileged. It sums up the whole city, he resumes, where “we’ve got some of the most celebrated architecture and history, wealth and privilege in the city centre, but you’ve got The Leys, Rose Hill and Barton – some of the most deprived areas in the country.”

The album also features an acoustic version of ‘Son Rise’, the original of which is on 2012’s Spoken. He wrote it when his partner was pregnant with his first son, penning the final verse the night he was born, “again using lyric writing as therapy – I was so overwhelmed by emotion.” His eldest boy is nine now, and into Fortnite, fitting given the line in ‘Son Rise’, “Hands off my PlayStation, your time will come, just be patient.”

I wonder how he prepares both his sons, the youngest of whom is four, for the world’s racism. His firstborn is similar in skin tone to him and his second is “pretty fair – he takes after my mum. Although they’re brothers,” he continues, “they’ve got the same parents and they’ve been raised in the same household, they’re both going to have different experiences of people judging them because of the colour of their skin. It’s something I want to prepare them for but at the same time I don’t want to make them paranoid and think, ‘everyone hates me because of my skin.’ I’ve had a few conversations with my older son about how some people have never met black people before and so get an idea that black people are this, this and this. They might be fearful or judge on what they’ve picked up through the media or some other source. That’s not something you should take on board as what you are,” he tells his child. “People will judge you on all sorts of things and you have to be sure enough in yourself and secure enough to know that even if someone’s saying bad things about you or treating you in a certain way, that’s their problem, not yours.”

With regards his youngest, “He’s like, ‘me and Mummy are peach and Daddy and my brother are brown.’ I’ve asked him, ‘how is it decided what colour you are?’ He says, ‘I don’t know, you’re just born a colour.’ He doesn’t see it as relevant to your heritage or your parents, he just thinks people are born different colours and that’s as far as he understands it. As he grows older I think I will start to have those conversations with him as well.”

Rawz’s mother is white and his father is black. He talks about the racism they both faced before he was born, the “horrendous stories” of which were told to him by his mum, who was even evicted once when the powers that be found out her boyfriend was black. “My mum didn’t want me to have to grow up in that world, so from a very young age she was always giving me positive examples of black people and teaching me about black history. As I got a little bit older she started a support group for parents with children of mixed heritage.” Thus, all his life he’s been aware of racism, against which he’s been involved in campaigns. “So when this new round of Black Lives Matter came about,” he says of this year’s events, “I had a week or so when I was quite depressed about it, like, ‘here we go again, it’s going to be flavour of the month and nothing’s going to happen.’” Added to which, he was upset by the All Lives Matter hashtag and those who took offence to the statement, Black Lives Matter. However, he says, as BLM gained momentum he began to think that things could perhaps change for the better.

He and I share a colleague in Dane Comerford, director of IF Oxford, of which Rawz is a trustee. IF funded one of his music projects, alongside Oxfordshire Youth Justice Service, which “had a lot of really positive outcomes for young people in The Leys”. That’s how he met Dane, who later asked to meet with him as part of the festival’s “key aim to engage with people who wouldn’t normally connect with science, i.e. people who live in The Leys who aren’t the usual customers of science museums. Basically, what he said was – without wanting to be rude about any of my fellow trustees – ‘we’re a bunch of largely middle-class white people, sitting in a room trying to imagine what people on The Leys want, and it feels wrong. Would you get involved to help us steer this thing and help us better engage with our target neighbourhood?’

“I’ve always been interested in science and passionately believe a lot of the adversity faced by people on The Leys is due to a lack of self-expectation – a lot of people feel like they can’t do any more than crime. I wanted to show young people and adults on The Leys that they can engage with science and be scientists themselves. They don’t have to go down any more of these stereotypical routes that Leys residents go down.”

He specifically mentions a 2018 IF Oxford event he went to with his sons, at Blackbird Leys Community Centre, “a trip to Wakanda, to visit a Wakandan science lab. They had a whole choreographed fight scene with Black Panther. One of the absolutely great things about that event, which made me 100 percent sure I wanted to be involved in the festival, was that there were so many children from The Leys coming in and talking to scientists from Harwell and University of Oxford, doing experiments with really well respected scientists. Also, the scientists were people of colour. Being able to show black children black scientists makes [a science career] a much more reachable goal for them. It demonstrates: ‘look, this person has the same colour skin as you and has probably experienced a lot of the same prejudices and knockbacks, but they’ve still made it and they’re doing this really cool experiment.’ That’s what IF Oxford is about – showing that there is a whole world of opportunity out there.”