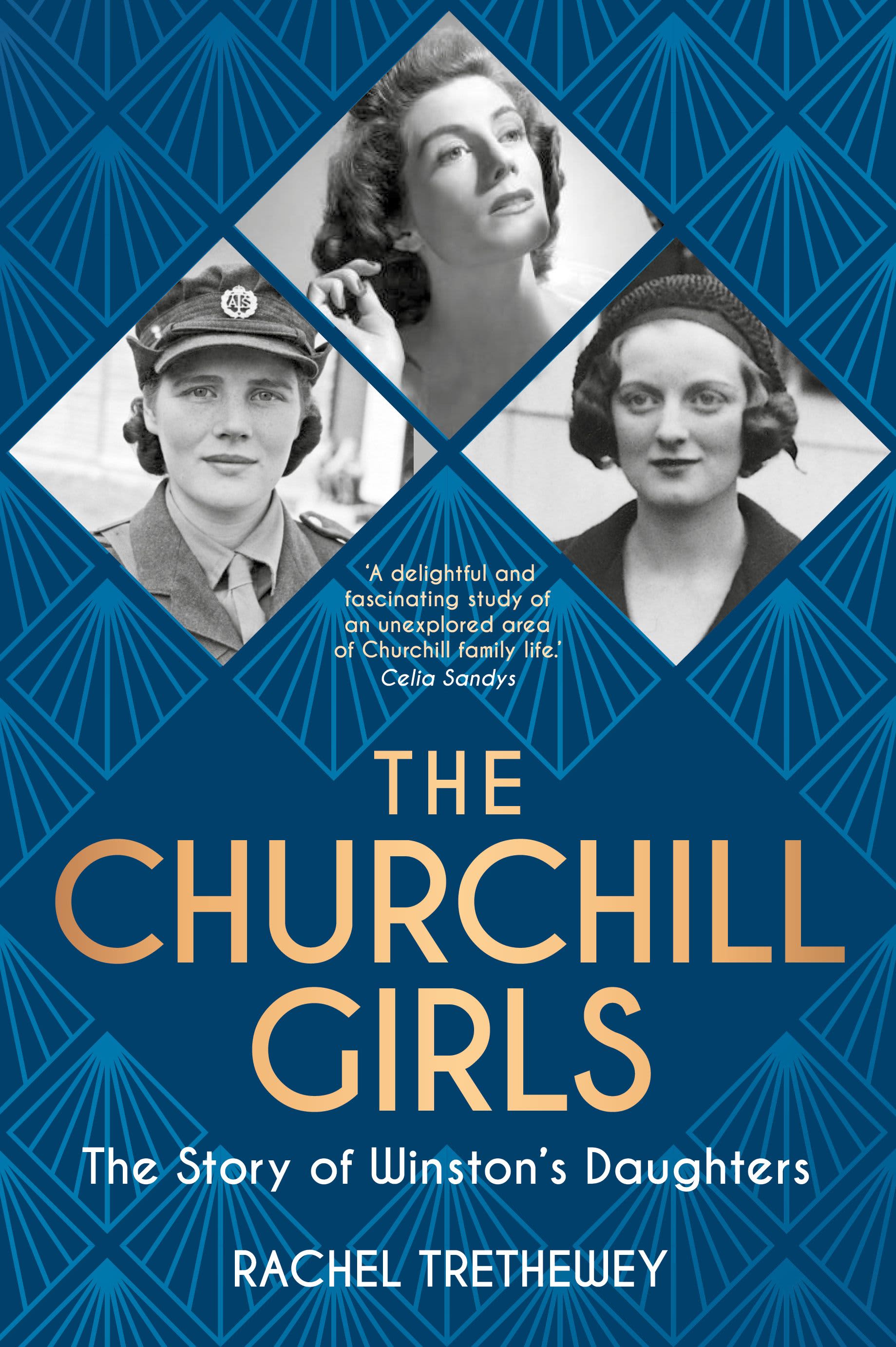

Bright, attractive and well-connected, in any other family the Churchill girls – Diana, Sarah, Marigold and Mary – would have shone. But they were not in any other family, they were Churchills and neither they nor anyone else could ever forget it. From their father to their golden boy brother Randolph, to their eccentric and exciting cousins, the Mitford girls, they were surrounded by a clan of larger-than-life characters which often saw them overlooked. While Marigold died too young to achieve her potential the other daughters lived lives full of passion, drama and tragedy. The Churchill Girls: The Story of Winston’s Daughters is the first biography of them. Divided into three parts, Childhood, War Years, and Post-War, this book intends to bring Diana, Sarah, Marigold and Mary out of the shadows and give them the attention they deserve. From her home study in Torquay, its author Rachel Trethewey tells Sam Bennett more about her behind-the-scenes insight into the Churchillian world.

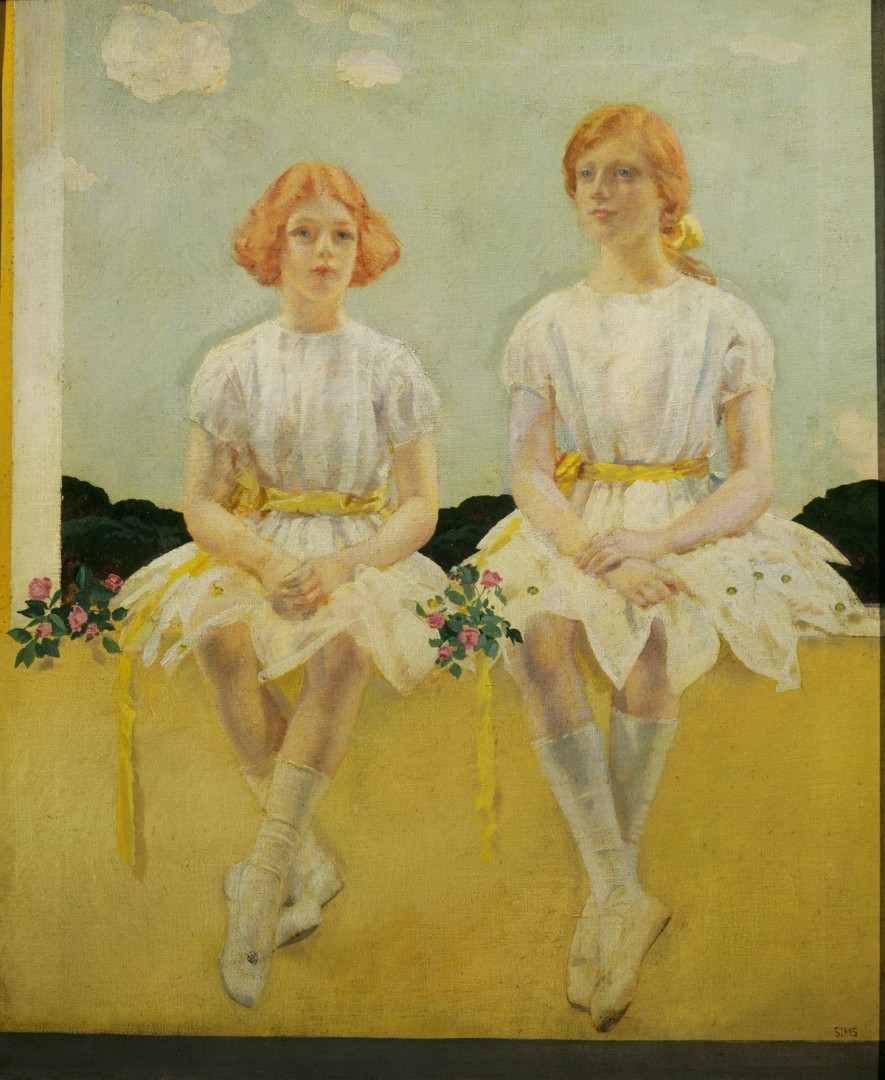

Oil painting on canvas, Two Girls Seated, Diana (1909-1963) and Sarah Churchill (1914-1982) by Charles H. Sims (Islington 1873-Boswells 1928), signed SIMS, 1922. Churchill was to say of the picture that he thought Diana looked ‘priggish’ and Sarah ‘rather impudent’, Chartwell © National Trust Images / Derrick E. Witty

Congratulations on the book which you ended up writing by chance, right?

Yeah, I think my books always sort of start like that. I’ll read something, and it sticks in my mind. I was researching another project about Churchill’s animals, so was looking through the Churchill archives, and I read this letter between Sarah and her father. I just thought, ‘Goodness, they had such a close relationship.’ I don’t know if I’d have spoken to my father like that. She’s telling him how she felt about men, about marriage, about children. It was so open, so colourful, she expressed her emotions so well, that I wanted to know more. And I found this really exciting story.

To what extent did you physically trace the steps of the Churchill girls? You must have been to Chartwell – the Churchill family home, now a National Trust property – but I’m also wondering about their extensive travels outside the UK. The family had very strong ties with America, for example.

Sadly, the final bit of writing it was during the pandemic, so I couldn’t get to America. The book is coming out in America in November, so I’m hoping I can get over there then. I was able to do most of the research before the pandemic hit, so of course I did go to Chartwell, I know Blenheim, and it was wonderful going to the Churchill archives in Cambridge. They have everything there, thousands of letters, memos, diaries – I found a report about Sarah’s alcoholism, from when she went to this clinic in Switzerland. Normally, I’d be able to do more footsteps, but it was slightly curtailed. In a way it’s been more about reading the girls’ thoughts and being able to draw on them.

The correspondence between their parents, Winston and Clementine, is fascinating. You write, “Diana was a particularly pretty baby, which pleased her competitive mother. She reported with pride to Winston about how their daughter compared with the six other infants who were visiting. She wrote, ‘None of them are fit to hold a candle to our P.K. [‘the Puppy Kitten’] or even to unloose the latchet of her shoe.’”

Clementine, particularly, commented on their looks and things like that. I suppose it was that sort of era, when girls were judged by how they’d do in the marriage market. Clementine was a highly intelligent woman and did really value female intelligence too, but when she was in competition… Diana found it hard because she felt she didn’t measure up to her mother's exacting standards. She thought she wasn’t slim enough, pretty enough, she thought Clementine thought Sarah was more attractive. I think that can be a problem between sisters, but the Churchill girls weren’t competitive among themselves. They did have problems – most of all Diana, and to a degree Sarah – with Clementine, but the three of them never bitched about each other. They were a unified force and always supportive of each other. There’s that story of when Diana was at a dress fitting, with Clementine and Sarah, and was upset when her mother commented that it was always so much easier to dress her younger daughter. Afterwards, Sarah was sensitive enough to know that would have upset Diana, and she said to her, “Mama didn’t mean it unkindly. She was trying to bolster me up.” There’s that sensitivity to each other all the time which I thought was really touching.

“Shallow society social life never appealed to Clementine or her girls,” you write, “because they had far more intellectual depth than the average aristocratic butterflies who flitted through the season.” Might life have been easier for the girls had they just been butterflies?

It might have been. They put pressure on themselves. There were great expectations if you were Winston’s daughters, and they just weren’t frivolous. I think that’s a reflection of their father, but also their mother sat there at debutante dances thinking, ‘This is so boring.’ It’s to all their credit that they felt there was a real purpose and duty in life – certainly Sarah had this real drive to achieve and express herself. They were in a very good position, the daughters of one of the most high-profile men in the country, they were attractive, but there was more to them. They were so multifaceted.

Facsimile of a photograph of Sarah Churchill beside a stone lion, in a leather frame, Chartwell © National Trust / Charles Thomas 2010

They all really played their part in the war effort.

They wanted their father and mother to be proud of them, and in the war, I think they were their most fulfilled – all three of them – because they felt they’d really done that. Diana had three children, so she was able to do less, but she did do a lot of voluntary work. The war allowed them to prove to their father what they could do, and that women do have a real role outside the home – I think it did alter his attitude to women’s roles.

You also write, “One of Winston’s most important lessons to his children was to be tolerant.” He is now, though, a somewhat controversial figure due to stories of his intolerance. This doesn’t seem to feature as a bone of contention between him and his daughters in the book, did they not call him out on it?

I think they probably didn’t because it was a different era. They were ahead of their time; he was of his time. That doesn’t excuse it, but it’s not something that seemed to come into any confrontation between them. I do confront why he didn’t like Vic Oliver [Sarah’s husband]. Every bit of evidence suggests it wasn’t because he was Jewish – in the 1930s Churchill did everything he could to protect Jews, I think it’s generally accepted he wasn’t anti-Semitic. Sarah did have battles with him about the men she liked, he never seemed to approve of her boyfriends, and they were more ‘rebellious’ choices than her sisters who went for the more standard establishment figures.

Winston was also a fun dad, wasn’t he? When they were young, he’d pretend to be a gorilla and chase them up trees.

He was fun, he got down to that level. They didn’t say a bad word about him. When asked in an interview if it was difficult being Winston Churchill’s daughter, Sarah laughed and said, “There’s no problem having him as a father. I wonder if he hasn’t found it a problem having me as a daughter.” They adored him.

Post-war seemed to have presented problems for both Winston and his daughters, as if without that purpose they felt a little lost.

That’s true. When there’s a major crisis, you don’t have to think about anything else, do you? You just have to get on, you don’t have much choice. So, it was clear in a way what they had to do. Once that was over, there wasn’t such a role for the girls, they had to go and carve their own niches, and Churchill was out of power in 1945 and it was immensely hard for him. He thrived on being at the centre of events and felt life was pretty much over for him when he was no longer prime minister. Finding a purpose in the post-war years was hard. Mary embraced it, but it was harder for Diana – her marriage broke down – and Sarah who nearly became massive in America; she was in films, on Broadway, much more famous in America than here, but she did have that alcohol problem. There were underlying problems they couldn’t quite escape.

Mary does seem to emerge from the book as something of the hero.

Mary has the perfect life in a lot of ways. She doesn’t put a foot wrong. I remember my publisher saying to me, “Could she really have been that happy?” I think she was. She had a great temperament. She had a different upbringing. In those early years, for Sarah and Diana it was quite a nomadic existence. The parents were living their own lives largely – the children were bunged off in different country houses – but when Mary came along (after Marigold’s death) they knew they had to get their act together and got Chartwell, a great base. So, Mary had stability growing up – and when Clementine was away, she had a very supportive nanny/governess figure in Maryott Whyte. Then she had a very happy marriage and successful war career. She had it all in a way, she lived this very traditional life but after her husband died, she had her own career too. She wrote a very successful biography of her mother and other successful books on the Churchills. She was involved in the National Theatre and made a Lady of the Garter. A complete life. However, I feel more for the vulnerable, Diana and Sarah. They were given the more difficult hand by fate, maybe, with their temperaments. It was really difficult being Diana, with her mental health problems, but if you needed someone, she’d be there for you – when Sarah’s husband Henry died in Granada, it was Diana who flew out to be with her. And I find Sarah particularly fascinating. I wouldn’t have wanted to write a biography just on Mary because it wouldn’t have the same highs and lows, and you can identify with the struggles of the others, can’t you?

Diana sadly took her own life. I wonder, had her struggle been today, whether things might have turned out happier due to advancements in mental health awareness – although the Churchills had a good understanding of mental health, for the time.

The family didn’t turn their back. After Diana had been away in a mental hospital, Churchill tried to really involve her in things and make her feel valued. But the treatment at that time – electroconvulsive therapy, insulin coma therapy – was barbaric and didn’t work. Also, there weren’t antidepressants. So yes, in a different era, with better treatment and less taboo, maybe the outcome would have been different.

Of course, her death was not the only tragedy the family faced. As you mentioned, Marigold passed away aged just 2 years and 9 months.

That shatters a family, losing a child like that. They handled it in the way of their era, I think. Clementine didn’t talk about it – Mary didn’t know about her sister until a lot later – she repressed that grief, rather than letting it out, it must have affected Winston too.

That’s also where the family are complex because there may be examples of ‘stiff upper lip’, but there are cases to the contrary. Mary even says to one interviewer, “We certainly weren’t examples of the stiff upper lip.”

That’s absolutely right, they did express their emotions as well. Mary and Winston had this incredible gift where they could tell a story and tears would come to their eyes. So, they did display emotion, very publicly for that era. That’s good, isn’t it?

Your book is about sisters and sisterhood – for me one of the most poignant moments being when Sarah writes to Mary, “we were really sisters” – and you also fittingly dedicate it to your sister.

Becca’s one of my first readers, always, and she’s really pleased it’s dedicated to her. Actually, it’s her 50th birthday in April, so I said, “Well, that’ll do as a present then.” Although I think she’s going to expect a bit more from me!

The Churchill Girls: The Story of Winston’s Daughters (The History Press) is available now.

Chartwell, National Trust

Family home and garden of Sir Winston Churchill

01732868381 | chartwell@nationaltrust.org.uk | Mapleton Road, Westerham, Kent TN16 1PS